Not the least of Rathnam’s subversive strategies in this very singular of films is the employment of a narrative ‘machine’ which introduces non-linear ‘shards’ to upset canonical expectations. The film offers a ‘revaluation’ of the Ramayana contours not by setting up a formal anti-text but by using gaps in the orthodox versions to insert Raavan’s text within them. The plot is therefore reconfigured at every turn almost surreptitiously. The flashback device has rarely been used more effectively because each time one emerges from one of these a bit more oriented toward the title character and his motivations, a bit more naturalized in his surroundings. It is also crucial to point out at the outset that this is also not an anti-Ramayana that renders Raavan more human or accessible. In fact the film always shrewdly maintains a certain distance toward him. Rathnam does not switch the places of the two central male protagonists as much as he interrogates the entire system of co-ordinates within which this opposition acquires minimal sense. Not surprisingly the film ‘happens’ in Raavan’s abode because it is only at this site that the ‘questioning’ can really come about. And while it is not ‘Sita’s tale’ the work is perspectivized through Ragini who offers the only possible access into Raavan’s realm. The entire framework allows Rathnam to formulate a startling political critique that might well be his most consistently sustained.

But every discussion of Raavan ought to begin with its visual schema which arguably highlights the director at his formalistic best. This kind of judgment might seem a bit hyperbolic for a master who has created so many seminal works in this regard but here for the very first time Rathnam also imagines an entire ‘new world’. All of Terence Malick’s pristine, virginal nature seems to be present in Raavan except that it is not rendered quasi-mystical as in the American director’s transcendental longings. Consequently Rathnam’s natural world is only a physical site which houses his characters and not the ‘house of being’ that it is for the Heidegger-soaked Malick. This ‘edge of the world’ setting is neither a mythic landscape of memory nor an Edenic site of nostalgia nor even a ‘sound and fury’ personification of the ‘nature’. It is only Raavan’s ‘other’ abode, a little mysterious much like him. This topological richness forms the entire physical space for the ‘story’. It is as if Rathnam intuits that real subversion in this tale is possible only when one moves out of Ram’s comfortable surrounding and starts dwelling in Raavan’s stranger environs. And perhaps appropriately for the themes of this movie there are always precipices and abysses round the corner. Always the possibility of a fall. Hence all sorts of horizon shots. A world where there is all the clutter of a tribal community in areas of dense foliage or tiny villages ensconced within but equally cascades and flowing water, moist rocky terrain that provides perching places for so many of the characters. It is almost never a level landscape. Characters appear geometrically on screen in various heights and postures. But there are always falls and drops dangerously lurking around the corner of a glance. This ‘challenging’ geography that Raavan inhabits mirrors perfectly the equally challenged ethos of his community. For it seems to be forever under siege by the forces of ‘Ram’.

Rathnam opens he film with a marvelously dynamic montage. He starts in medias res and there is almost nothing of Raavan in the movie that is not mediated through Ragini’s perspective. In other words we never see a Raavan that she does not. In fact looking at many of the earlier stills one realizes that the director moved even more in this direction as time went on. But Raavan remains somewhat other to us as he does to Ragini and the edits reflect this. At the same time the camera also captures all the immediacy and visceral qualities of these new surroundings for Ragini, all the ways in which her motor responses are perhaps always more unhinged in her state of captivity and the extent to which she can always be unsettled by human company. If Ram Gopal Varma’s films have often privileged a longitudinal destabilization Rathnam here while doing a fair bit of this is also equally interested in lateral displacement. Even as there are ‘vertigo’ shots and all kinds of high/low angles there are even more effectively executed swipes and flicks. This is essentially important because while physical height and the possibility of ‘falling’ is always a factor in this work there is the additional one of Ragini imprisoned in a setting where she usually finds Beera in her ‘orbit’. The touchstone moment here and which might also be considered the film’s supreme visual trope occurs when Beera in a scene of exquisite erotic tension encircles Ragini with one hand blocking her face, one her chest, and then his face constantly getting closer to her, all this without ever touching her. Meanwhile the camera itself encircles the pair and moves with them and even closes up on them at one point. A kind of ‘mimicry’ moment that is positively unique specially with the stunning soundtrack playing an alternate version of Ranjha almost as an alien sound. If Macbeth’s witches could have been given this song the result might have been approximately this. It makes for mesmerizing cinema and really reminds one of a scene in Red Desert (Antonioni) when the girl goes out to swim and a rather unsettling female vocal strain suddenly erupts. The song in Raavan itself works like a shard from the original, it seems to convey a sense at once primeval and post-apocalyptic. Eventually of course this is connected with strains from the original song in a flashback which then connects this gorgeous scene to the trauma of the past. The visual and sound cues are extraordinarily well-matched in the moment. Elsewhere there are superb tracks, hand-held gravitational shots, sparingly used wide angles that emerge with a certain force because the viewer is so acclimatized to relatively tight frames. This is not a claustrophobically shot work but it is also not one of dazzling vistas. Rathnam and Sivan create a very neat economy between the two and the marriage between thematic intention and visual translation is near-perfect.

The very same could be stated for what seems to be the most extraordinary of Rahman’s background scores. The soundtrack veers mostly on the experimental and only occasionally reveals more familiar cues. The mix is quite intoxicating and the significance of Rahman’s work in the film’s overall texture of image, sound and sense can scarcely be overstated. Oddly though the songs are perhaps not as effectively used as elsewhere in Rathnam probably because the tone of this narrative never really allows those easy transitions. This does not rise to the level of a complaint but contrasted with the fabulous background work the ‘formal’ songs seem lesser within the body of the film.

The camera does not just frame Raavan in the film but the Beera Ragini always ‘witnesses’ in some form or fashion. This is a crucial point which might also explain some of the problems many have had in gauging Abhishek’s performance. It is not that his is an underwritten character but of necessity a somewhat mysterious one because he can only be represented by way of the female protagonist. This is not at all true for Ram who is shown independently in many moments. The comparable ones are very few for Beera and of a certain contingent sort. The overall principle holds. Even as Ragini grows to understand Beera, even as she is drawn to him (though this is represented very subtly as opposed to Beera’s own attraction to her), even as she definitely grows to care for him she can never completely ‘know’ him. He is always a bit of a shadow to her, the very silhouette he is introduced as and often framed as through the course of the film. Abhishek’s performance is actually very even here even if the introduction of certain psychological ticks to the character seemed less necessary. But this is not a fault with a performance that is beautifully keyed to the tone of the film and the mystery of Beera’s world. As the film progresses Beera gets more vocal and when he is most in confessional mood the end has arrived for him. Ragini allows Beera to develop certain registers of language. On the other side of this equation her immersion in Beera’s universe allows her to comprehend the violence that the Devs of the world have inflicted on it and from being repelled by the violence of the former she is eventually even empathetic to it, understanding it perhaps as a ‘positive’ response to the ‘oppressor’. Rathnam in this sense does not have a formal political program but he is certainly polemical enough in unmasking the presumptions of bourgeois complacency. Beera’s community represents the displaced and the marginalized. Rathnam in turn ‘places’ their violence within context. There are unsettling moments of violence in the film that almost always make Dev and his ‘confederates’ seem less sympathetic. As an aside one should add point to an obvious example — those recent events of mind-numbing Maoist violence and the bourgeois imagining of the same as occurring in a vacuum with no political contexts. Dil Se to this degree is the complementary film to Raavan.

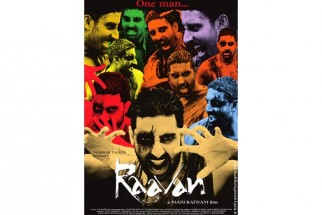

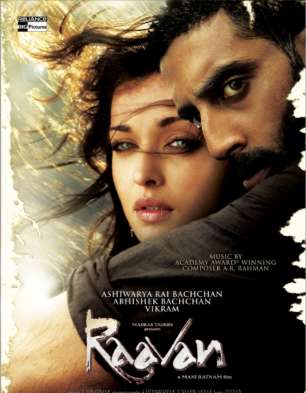

This is arguably Aishwarya Rai’s best part. The charismatic center of the film remains quite naturally Beera but her character is the ‘soul’ of the film and as mentioned before the viewer’s guide. An always engaging performance on her part that also usefully incorporates her star signature. It would be hard to argue for superior casting for her part. Vikram who forms perhaps the truer complement to Abhishek is despite the limitations of his part in fine form here. In fact rarely has the actor been more economical than in this film. It is a part with not much variation at all but Vikram conveys everything important about this character very quickly into the film and he is always arresting to behold. Abhishek finally is the film’s enigmatic and ultimate ‘signifier’. It is his world and his ‘order’ that Rathnam intends to explore. Dev’s ‘civilization’ is transported to his ‘anarchy’ by way of Ragini and the inversion begins. He is the center of Ragini’s fascination eventually, he is certainly at the heart of Dev’s obsession but he is also a character importantly in dialogue with himself on key occasions, a somewhat unhinged soul presumably offered by Rathnam as a byproduct result of Dev’s impulses. Ram in a sense begets Raavan. Abhishek in any case is perfectly attuned to all the cross-currents of this narrative. The actor reveals formidable range in his part but this is an ‘auteurist’ work not meant to be one where the actor can ‘take over’ Guru-like. In missing this point one risks missing an encounter with the film itself.

And so one gets to the extended finale. A brilliantly executed fight on a bridge and the truly scintillating aftermath. Here Dev’s ambiguity is more truly revealed even as Beera is definitely humanized a great deal. One leaves the film moved by Raavan but in unease about Ram. The aftermath portions condense the film and there is not a hero and villain at the end of it, just two modes of violence, neither of which one can completely embrace, each of which one can empathize with in parts. Rathnam nonetheless is more invested in Beera, as is Ragini, as are we. Beera passes away with a certain ‘happy knowledge’ about Ragini and the audience is left wondering about what kind of a marital future she now has with Dev. Beera first emerges Nosferatu-like on a boat and finally falls with an inner peace into the abyss but also triumphant over Dev. Sita’s tale? Not really. But only she knows the truth of the Ramayana.. and there are some words she has never said..

[[couldn't really incorporate this into the flow of the piece but the supporting cast is simply superb here in every single instance.. a treat to watch one and all.. and of course there are other aspects of the film that could be discussed

New notification